C Linux Master Sheet

C interview cheatsheet of important questions.

Make sure to revise the list right before an important interview

Important C macros

Basic macros

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#define MAX(a, b) ((a) > (b) ? (a) : (b))

#define MIN(a, b) ((a) < (b) ? (a) : (b))

#define ABS(x) ((x) < 0 ? -(x) : (x))

#define IS_POWER_OF_TWO(num) ((num) > 0 && ((num) & ((num) - 1)) == 0)

#define SWAP(x,y) (x ^= y ^=x ^= y)

#define IS_EVEN(num) (((num) & 1) == 0)

#define IS_ODD(num) (((num) & 1) != 0)

#define SWAP(x,y,T) do { \

T temp = (*x);\

(*x) = (*y); \

(*y) = temp; \

} while (0)

Bitwise macros

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

#define SET_BIT(num, i) ((num) |= (1 << (i)))

#define CLEAR_BIT(num, i) ((num) &= ~(1 << (i)))

#define TOGGLE_BIT(num, i) ((num) ^= (1 << (i)))

#define CHECK_BIT(num, i) (((num) & (1 << (i))) != 0)

/* how to extract specific bits from, say, a 32-bit value */

#define EXTRACT_BITS(value, start, length) \

(((value) >> (start)) & ((1U << (length)) - 1))

#define COUNT_SET_BITS(num) ({ \

int _count = 0; \

int _num = (num); \

while (_num) { \

_num &= (_num - 1); \

_count++; \

} \

_count; \

})

Structure and type macros

1

2

3

4

5

6

#define SIZEOF(type) ((char *)(&type + 1) - (char *)(&type))

#define SIZEOF_TYPE(type) ((char *)((type *)0 + 1) - (char *)((type *)0))

/* Find offset value of a member of a structure */

#define OFFSET_OF(type, member) ((size_t) &(((type *)0)->member))

List macros

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

#define LIST_FOREACH_SAFE(head, node) \

for (struct ListNode *node = (head), *__temp = (node ? node->next : NULL); \

node != NULL; \

node = __temp, __temp = (node ? node->next : NULL))

/* Not delete safe */

#define LIST_FOREACH(head, node) \

for (struct ListNode *node = (head); node != NULL; node = node->next)

/* Find length of LL */

#define LIST_LENGTH(head, len) \

do { \

(len) = 0; \

struct ListNode *node = (head); \

while (node) { \

(len)++; \

node = node->next; \

} \

} while (0)

Other macros

1

#define IS_LITTLE_ENDIAN() ((*(char *)&(int){1}) == 1)

Function Pointers and Callbacks

Function Returning a function pointer usage

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

#include <stdio.h>

typedef int (*OperationFunc)(char);

OperationFunc additionFunction(int x)

// Function that returns a function pointer

int (*additionFunction(int x))(char) {

int add(char c) {

return c;

}

return add;

}

int main() {

// Get the function pointer from the outer function

int (*sumFunc)(char) = additionFunction(10); //This will call the function "additionFunction"

// Call the function using the function pointer

int result = sumFunc('A');

printf("Result: %d\n", result); // Output: Result: 85 (ASCII value of 'A' is 65, 10 + 65 = 75)

return 0;

}

Callback example programs to register ops

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

#include <stdio.h>

typedef struct sample_ops {

int data;

void (*print)(int);

} sample_ops;

void printer(int a) {

printf("Print %d\n", a); // Added the missing argument a

}

int main() {

// Write C code here

static const sample_ops my_ops = {

.data = 60, // Replaced ; with ,

.print = printer

};

my_ops.print(my_ops.data);

return 0;

}

Tricky Code snippets

Find Length of linked list

1

2

int len=0;

for (struct ListNode *i = head; i; i=i->next, len++);

💡 Only one TYPE of variable can be declared in for loop init section. So we cant declare

lenthere. In the second and third place holder of for loop, we can have multiple statements separated by comma. The below example declares two variables of same type and it is VALID.

1

for (int i = 0, sum = 0; i < n; i++) {

2D Array Allocation and Free

💡 dp[0][0] conversion to *((dp+0)+0)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int rows = 3, cols = 4;

int** array = malloc(rows * sizeof(int*)); // Allocate memory for row pointers

if (array == NULL) {

perror("Memory allocation failed");

return 1;

}

for (int i = 0; i < rows; i++) {

array[i] = malloc(cols * sizeof(int)); // Allocate memory for each row

if (array[i] == NULL) {

perror("Memory allocation failed");

return 1;

}

}

// Access elements

array[1][2] = 42; // Example usage

printf("Value at array[1][2]: %d\n", array[1][2]);

// Free memory

for (int i = 0; i < rows; i++) {

free(array[i]); // Free each row

}

free(array); // Free the row pointers

return 0;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int rows = 3, cols = 4;

int* array = malloc(rows * cols * sizeof(int)); // Single block for all elements

if (array == NULL) {

perror("Memory allocation failed");

return 1;

}

// Access elements using index calculations

array[1 * cols + 2] = 42; // Equivalent to array[1][2] in a "normal" 2D array

printf("Value at array[1][2]: %d\n", array[1 * cols + 2]);

// Free memory

free(array);

return 0;

}

3D Array Allocation and Free

Linux Kernel Synchronization Techniques

- Multiple threads can run simultaneously on modern SMP systems (CONFIG_SMP=y) or Single core systems with CONFIG_PREEMPT enabled

- This introduces race condition problem where two threads race to access and modify a single variable. There is no guarantee that the threads will modify the variable as expected. Behavior is undefined.

- On such systems and scenarios where such a condition is encountered , we need to synchronize the two threads to make sure that they modify the shared variable , one at a time

Mutex

https://docs.kernel.org/locking/mutex-design.html

Mutex enforces serialization on shared memory systems(serial access meaning one at a time). Mutexes are sleeping locks which behave similarly to binary semaphores.

Mutexes are represented by ‘struct mutex’, defined in include/linux/mutex.h and implemented in kernel/locking/mutex.c

Mutexs have ownership. mutex→owner store the thread owning the mutex. Any modifications to the thread must be done by same thread.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

struct mutex {

atomic_long_t owner;

spinlock_t wait_lock;

#ifdef CONFIG_MUTEX_SPIN_ON_OWNER

struct optimistic_spin_queue osq; /* Spinner MCS lock */

#endif

struct list_head wait_list;

#ifdef CONFIG_DEBUG_MUTEXES

void *magic;

#endif

#ifdef CONFIG_DEBUG_LOCK_ALLOC

struct lockdep_map dep_map;

#endif

};

Contents of mutex Linux Kernel structure

🔹 atomic_long_t owner

- Purpose: Stores a reference to the current owner thread of the mutex.

- Use:

- Detect recursion (same thread trying to relock).

- Used in

mutex_trylock()and lock debugging.

NULL(or 0) means no one owns the mutex.

🔹 spinlock_t wait_lock

- Purpose: Protects the wait list (below).

- Use: Ensures atomicity when updating or walking through the list of waiting tasks.

- Lightweight and fast lock for short critical sections.

🔹 struct list_head wait_list

- Purpose: Holds tasks that are blocked, waiting for the mutex. (list_head is a commonly used DLL gluebased list in kernel)

- Use: When a thread tries to acquire a held mutex, it’s put on this list.

- Used in

mutex_lock()when a task sleeps waiting for the lock.

🔹 struct optimistic_spin_queue osq (under CONFIG_MUTEX_SPIN_ON_OWNER)

- Purpose: Enables spin-then-sleep optimization.

- Use: If a task thinks the owner will release the mutex soon (still running), it spins briefly instead of sleeping.

- This improves performance on multicore systems under contention

🔹 void *magic (under CONFIG_DEBUG_MUTEXES)

- Purpose: Used for internal debugging to detect corruption.

- Use: A known magic value is stored; if it’s wrong later, something corrupted the mutex.

🔧 Only compiled in when:

🔹 struct lockdep_map dep_map (under CONFIG_DEBUG_LOCK_ALLOC)

- Purpose: Used by lock dependency checker (

lockdep) to detect deadlocks. - Use: Tracks lock acquisition ordering between different locks.

- Helps detect potential AB-BA deadlocks (A → B and B → A).

The mutex subsystem in Linux Kernel checks and enforces the following rules:

- Only the owner can unlock the mutex.

- Multiple unlocks are not permitted.

- Recursive locking/unlocking is not permitted.

- A mutex must only be initialized via the API (see below).

- A task may not exit with a mutex held.

- Memory areas where held locks reside must not be freed.

- Held mutexes must not be reinitialized.

- Mutexes may not be used in hardware or software interrupt contexts such as tasklets and timers.

API for Linux Kernel Mutex

Statically define the mutex:

DEFINE_MUTEX(name);

Dynamically initialize the mutex:

mutex_init(mutex);

Acquire the mutex, uninterruptible:

void mutex_lock(struct mutex *lock);

void mutex_lock_nested(struct mutex *lock, unsigned int subclass);

int mutex_trylock(struct mutex *lock);

Acquire the mutex, interruptible:

int mutex_lock_interruptible_nested(struct mutex *lock,

unsigned int subclass);

int mutex_lock_interruptible(struct mutex *lock);

Acquire the mutex, interruptible, if dec to 0:

int atomic_dec_and_mutex_lock(atomic_t *cnt, struct mutex *lock);

Unlock the mutex:

void mutex_unlock(struct mutex *lock);

Test if the mutex is taken:

int mutex_is_locked(struct mutex *lock);

Disadvantages

Unlike its original design and purpose, ‘struct mutex’ is among the largest locks in the kernel. E.g: on x86-64 it is 32 bytes, where ‘struct semaphore’ is 24 bytes and rw_semaphore is 40 bytes. Larger structure sizes mean more CPU cache and memory footprint.

When to use mutexes

Unless the strict semantics of mutexes are unsuitable and/or the critical region prevents the lock from being shared, always prefer them to any other locking primitive.

Where not to use mutex:

Interrupt context — mutex sleeps! Use spinlock_t instead.

Atomic context / softirqs — not allowed.

Practical Examples of Mutex in Kernel Driver implementation.

- Kernel Ring Buffers - Producer consumer scenario. Say a shared skb buffer

1

2

skb_queue_tail(&dev->tx_queue, skb); // Producer

skb_dequeue(&dev->tx_queue); // Consumer

Internally, these use spinlock (for performance) or mutex if the context allows sleeping.

-

Common ring buffers

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

struct ring_buffer { char buf[1024]; size_t head, tail; struct mutex lock; }; struct ring_buffer rb; mutex_lock(&rb->lock); // read or write to buffer mutex_unlock(&rb->lock);

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

void produce(struct ring_buffer *rb, char c) { mutex_lock(&rb->lock); rb->buf[rb->head++] = c; if (rb->head >= sizeof(rb->buf)) rb->head = 0; mutex_unlock(&rb->lock); } char consume(struct ring_buffer *rb) { char c; mutex_lock(&rb->lock); c = rb->buf[rb->tail++]; if (rb->tail >= sizeof(rb->buf)) rb->tail = 0; mutex_unlock(&rb->lock); return c; }

Self-deadlock Concept

Self-deadlock is a where the thread which has already acquired the lock, tried to reacquire the lock again.(Recursive locking)

1

2

3

mutex_lock(&my_lock);

// Some code...

mutex_lock(&my_lock); // Oops! Same thread trying to lock it again

Recursive Locking Concept

Recursive locking allows the same thread to acquire the same lock multiple times without causing a deadlock.

In complex systems or deep call chains, a thread might:

- Hold a lock in a caller function.

- Call another function (deeper in the call stack) that also tries to acquire the same lock.

Without recursive locking, this would deadlock.

With recursive locking, the system tracks how many times the lock has been acquired and only fully releases it when the lock is released the same number of times.

How Recursive Mutex Works

- Every time the same thread locks it, an internal counter is incremented.

- Each

unlock()call decrements the counter. - The mutex is only fully released (and available to other threads) when the counter hits zero.

Available in pthreads but not by default, you need to declare mutex attribute object and set the recursive flag to enable recursive mutex

Circular deadlocks Concept

A series of tasks waiting on the next one in a circular manner.

- Task A is waiting on Task B,

- Task B is waiting on Task C,

- Task C is waiting on Task A.

Mutex Lock and Unlock Paths

| Lock Path | Lock State | Action | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Path | Unlocked | Immediate acquisition | ✅ Best |

| Mid Path | Locked, short wait | Spin (busy wait) | ⚖️ Medium |

| Slow Path | Locked, long wait | Sleep & wake up later(context switch) | 🐢 Worst |

undefined | Unlock Path | Waiters | Action | Performance | | ———– | ——- | ————————— | ———– | | Fast Path | No | Clear owner, mark unlocked | ✅ Best | | Slow Path | Yes | Wake up one or more waiters | 🐢 Slower |

undefined When unlocking a mutex that has waiters, the Linux kernel tries to wake up the highest-priority waiter, not just the one that has waited the longest.

Mutex, Semaphore and Spinlock

**Semaphore**: Use a semaphore when you (thread) want to sleep till some other thread tells you to wake up. Semaphore ‘down’ happens in one thread (producer) and semaphore ‘up’ (for same semaphore) happens in another thread (consumer) e.g.: In producer-consumer problem, producer wants to sleep till at least one buffer slot is empty - only the consumer thread can tell when a buffer slot is empty.

**Spinlock**: Use a spinlock when you really want to use a mutex but your thread is not allowed to sleep. e.g.: An interrupt handler within OS kernel must never sleep. If it does the system will freeze / crash. If you need to insert a node to globally shared linked list from the interrupt handler, acquire a spinlock - insert node - release spinlock

Complex Declarations

Variable Declarations

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

1. int p; // An integer

2. int p[5]; // An array of 5 integers

3. int *p; // A pointer to an integer

4. int *p[10]; // An array of 10 pointers to integers

5. int **p; // A pointer to a pointer to an integer

6. int (*p)[3]; // A pointer to an array of 3 integers

7. int (*p)(char *); // A pointer to a function a that takes an integer

8. int (*p[5])(int); // An array of 5 pointers to functions that take an integer argument and return an integer

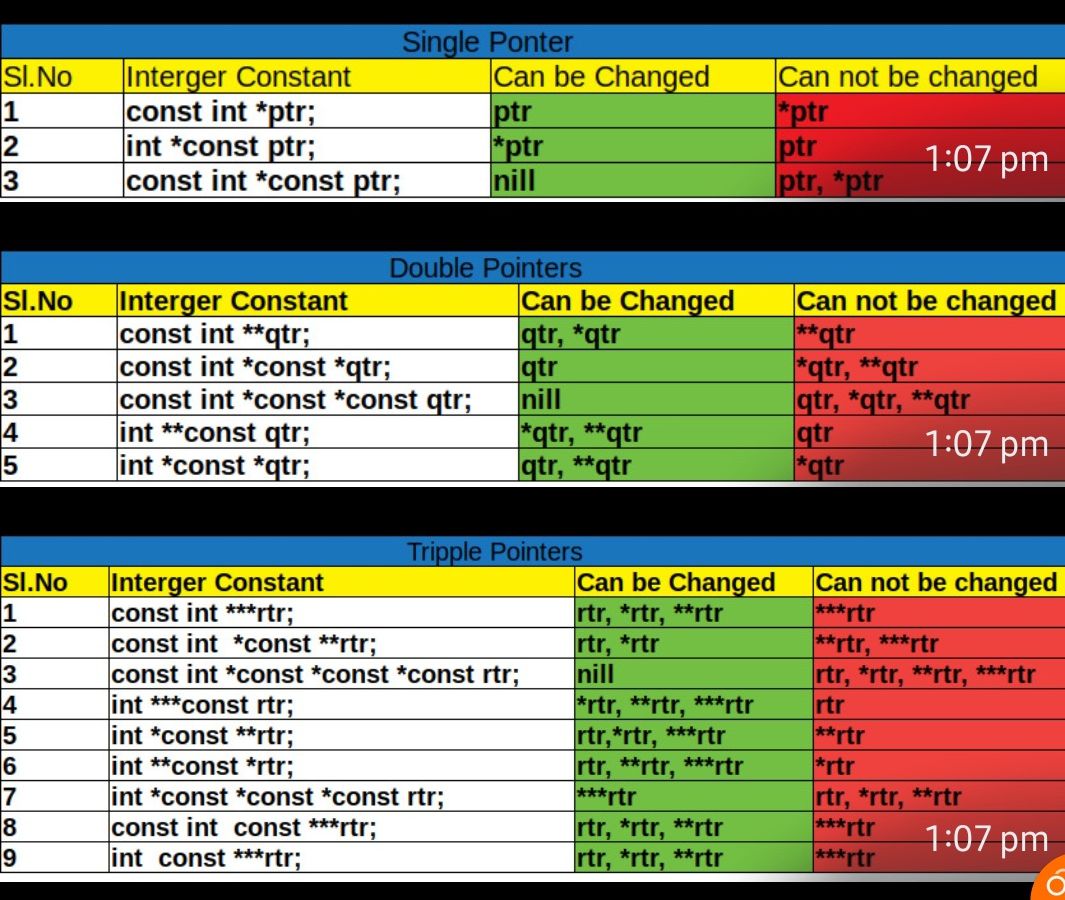

Single, Double and Triple Pointers with type qualifier

Pointer to Array

1

int (*arr)[10];

Array of pointers or 2D Arrays

1

int *p[10];

1

2

3

4

5

6

int array[5][13]; // A 2D array with 5 rows and 13 columns

int dp[rows][cols];

void func(int rows, int cols, int dp[rows][cols]);

void func(int rows, int cols, int dp[][cols]); // Rows can be omitted

int (*eaytb)[13]; // Pointer to an array of 13 integers

eaytb = array; // Pointing eaytb to the first row of the arra

In this case, eaytb can be used to access the rows of the array. For instance, (*eaytb)[0] would give you the first row of the array, while (*eaytb)[1] would give you the second row, and so on.

Passing

Comparison Table:

| Method | Memory Layout | Indexing | Ease of Passing | Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Allocation | Contiguous | dp[i][j] |

Easy | Fixed size at compile-time |

| Contiguous Memory (1D) | Contiguous | dp[i * cols + j] |

Requires manual indexing | Flexible runtime size |

| Pointer-to-Pointer | Non-contiguous | dp[i][j] |

Easy | Flexible runtime size |

| Variable-Length Arrays | Contiguous | dp[i][j] |

Easy | Flexible runtime size (C99+) |

undefined- Static arrays: Use for fixed-size arrays known at compile-time.

- Flattened 1D arrays: Use for dynamic size with contiguous memory for better cache performance.

- Pointer-to-pointer: Use when rows need independent allocation or resizing.

- VLAs: Use for flexible sizes if your compiler supports C99 or later.

C Basic Data Type Sizes and Format Specifiers

| Data Type | Memory (bytes) | Range | Format Specifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| short int | 2 | -32,768 to 32,767 | %hd |

| unsigned short int | 2 | 0 to 65,535 | %hu |

| unsigned int | 4 | 0 to 4,294,967,295 | %u |

| int | 4 | -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647 | %d |

| long int | 4 | -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647 | %ld |

| unsigned long int | 4 | 0 to 4,294,967,295 | %lu |

| long long int | 8 | -(2^63) to (2^63)-1 | %lld |

| unsigned long long int | 8 | 0 to 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 | %llu |

| signed char | 1 | -128 to 127 | %c |

| unsigned char | 1 | 0 to 255 | %c |

| float | 4 | - | %f |

| double | 8 | - | %lf |

| long double | 12 | - | %Lf |

undefined

What is the output of below code?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

const char normal[] = "stdout ";

const char error[] = "stderr ";

fprintf(stdout,normal);

fprintf(stderr,error);

fprintf(stdout,normal);

fprintf(stderr,error);

fprintf(stdout,normal);

fprintf(stderr,error);

putchar('\n');

return(0);

}

1

stderr stderr stderr stdout stdout stdout

The reason is that stderr are not buffered, whereas stdout is always buffered and output when buffer is full or during a new line character.

FORK

fork() split the program flow into two processes. The commands following after the fork will be executed by two different processes. (Program will be split)

1

process = fork()

- process value is 0 in child process.

- It is 1 in parent process.

Extract IP from a 32byte array

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

#include <stdio.h>

void extract_ip(uint32_t ip) {

// Extract each octet by shifting and masking

uint8_t octet1 = (ip >> 24) & 0xFF; // First 8 bits

uint8_t octet2 = (ip >> 16) & 0xFF; // Next 8 bits

uint8_t octet3 = (ip >> 8) & 0xFF; // Next 8 bits

uint8_t octet4 = ip & 0xFF; // Last 8 bits

// Print the extracted IP address in dotted decimal format

printf("%d.%d.%d.%d\n", octet1, octet2, octet3, octet4);

}

int main() {

uint32_t ip = 3232235776; // 192.168.1.0

extract_ip(ip);

return 0;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

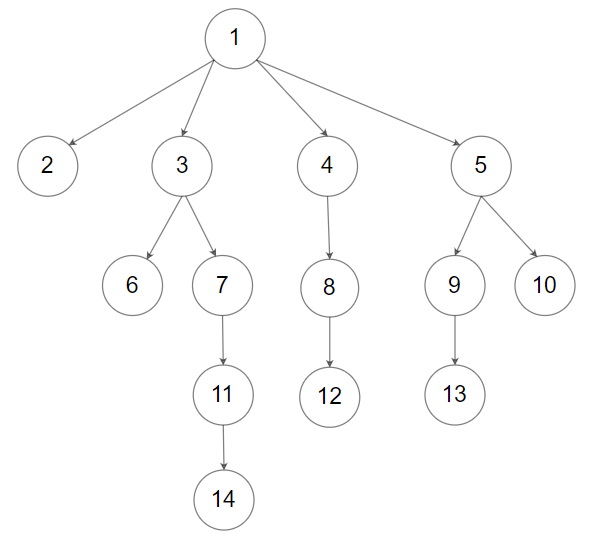

int maxDepth(struct Node* root) {

if (!root) return 0;

if (root->numChildren == 0) return 1;

int max=0;

for (int i=0;i<(root->numChildren);i++){

int temp = maxDepth(root->children[i]) +1;

max = temp > max ? temp : max;

}

return max;

}

Find intersection of LL

Guess the Output

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// Online C compiler to run C program online

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Write C code here

int a=10;

printf("a=%d\n",sizeof(a++));

printf("new a = %d\n",a);

return 0;

}

_p++ vs (*_p)++ vs *p++

* (dereference) has higher precedence than ++ (post-increment).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int arr[] = {10, 20, 30};

int *p = arr;

printf("%d\n", *p++); // Dereference, then increment pointer

// means print *p

// then do p++

printf("%d\n", *p);

return 0;

}

// output

//10

//20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int arr[] = {10, 20, 30};

int *p = arr;

printf("%d\n", (*p)++); // Dereference, then increment pointer

// print (*p)

// then do (*p) = (*p)++

printf("%d\n", *p);

return 0;

}

//output

//10

//11

Struct padding

Day 5: Bit Fields in C – Packing Data at the Bit Level

Bit fields in C provide a memory-efficient way to store small values within a single integer by specifying the exact number of bits a variable should use. This is useful in low-level programming, embedded systems, and protocols where memory is critical.

➧ What Are Bit Fields?

Instead of allocating a full int (usually 4 bytes or 32 bits), bit fields let you define variables with precise bit-width inside a struct.

====================================

Defining Bit Fields

struct {

unsigned int flag:1; // 1 bit for a flag

unsigned int mode:2; // 2 bits for mode (0-3)

} s;

s.flag = 1; // Stores 1 in a single bit

s.mode = 2; // Stores 2 using 2 bits (binary: 10)

====================================

flag:1 → Uses 1 bit (0 or 1).

mode:2 → Uses 2 bits (0 to 3).

The compiler packs these fields efficiently into an int.

➧ Using Bit Fields

====================================

int f = s.flag; // Reads 1

s.mode = 3; // Sets mode to 3 (binary: 11)

====================================

Bit fields behave like normal struct members.

The compiler manages masking and shifting automatically.

➧ Real-World Example – Network Packets

====================================

struct Packet {

unsigned int type:4; // 4 bits: 0-15 for packet type

unsigned int len:6; // 6 bits: 0-63 for length

} pkt = {5, 42}; // Type = 5, Length = 42

====================================

type:4 fits 0-15 in 4 bits.

len:6 fits 0-63 in 6 bits.

The struct is only 10 bits instead of 64 (if using full int values).

➧ Pros & Cons

Pros:

Memory-efficient → Uses only the required bits.

Ideal for hardware → Registers, protocol headers, etc.

Faster access → Smaller structures improve performance.

Cons:

Portability issues → Bit order depends on compiler/hardware.

No direct addressing → &s.flag won’t work.

Signed values → Behavior varies due to sign extension.

➧ Where Are Bit Fields Used?

Embedded Systems → Hardware registers.

Networking → Flags, headers, protocol data.

Data Compression → Packing multiple values efficiently.

Bit fields are powerful but require careful use. How do you use them in your projects?